Bloomberg CityLab

November 15, 2022

In the waning hours of US midterm elections last week, a Chinese American couple in their 70s in Philadelphia’s Chinatown voted for the third time in their lives. They were eager to do so, but Cun Jun Zheng and Shu Xiang Wang needed help to cast their ballots.

Afterwards, they stood outside the Chinatown church transformed into a poll site. Voting is a “sacred” duty, said Wang, who immigrated from China. She became a US citizen in 2016 with help from AAU, which also registered her to vote. Wang cast her ballot for the first time in 2016 and urged her husband to do the same.

“For us Chinese, it is especially important to vote,” said Zheng, a retired restaurant worker who came to the US in 1986. “There’s a lot of racism in our country. We need better leaders.”

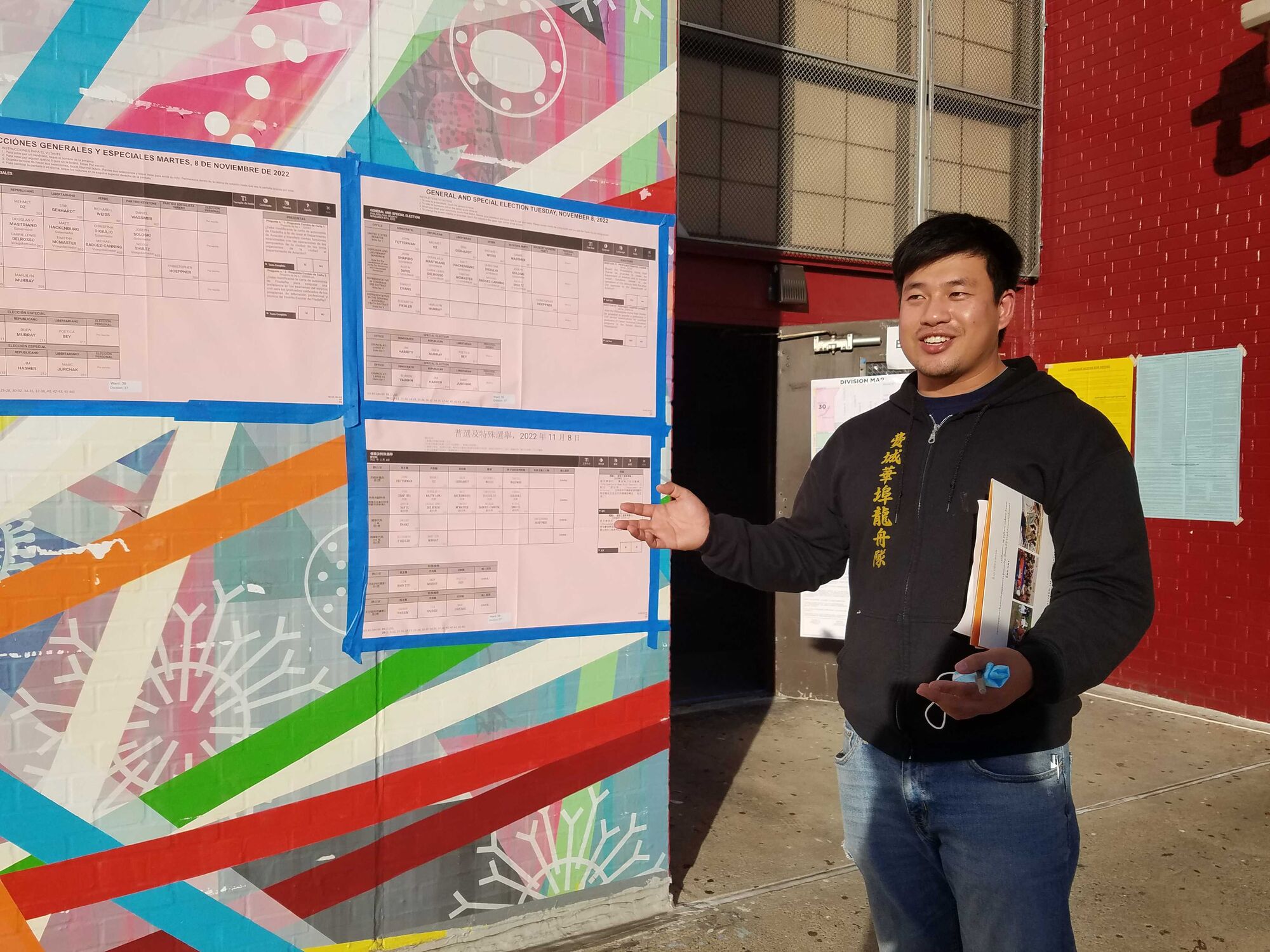

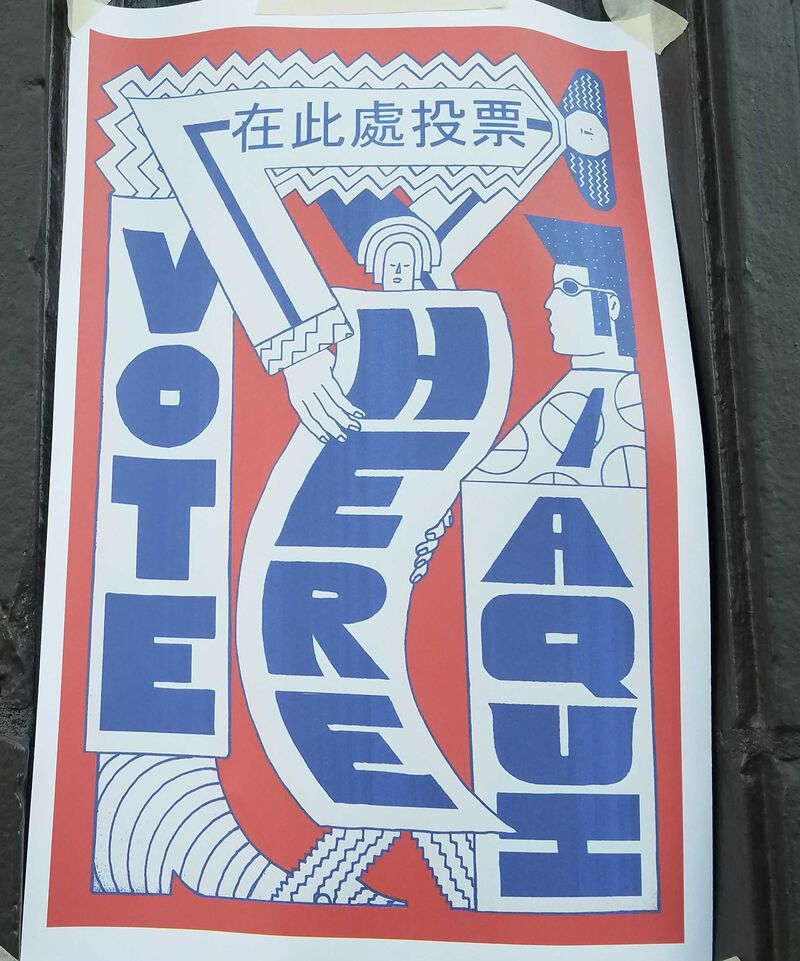

This year was the first time that federal law required Philadelphia to offer voting information in Chinese, as well as interpreters at poll sites and other language accommodations, under Section 203 of the Voting Rights Act. The law requires cities or counties to provide language assistance when more than 10,000 residents or over 5% of voting-age citizens have limited English proficiency, taking into account other factors such as education levels.

“This is a right for voters. Language access is social justice,” said Chen.

Yet the couple agreed that despite the city’s accommodations, they still could not have voted without Chen’s hands-on assistance.

In the battleground state of Pennsylvania, voters ultimately helped John Fetterman flip its Senate seat to Democrats in one of the most hard-fought races in the country, and also elected Democrat Josh Shapiro as governor. It’s likely Asian American voters made a difference: Nationally, 44% think of themselves as Democratic, 19% as Republican and 29% as independent, according a survey by the advocacy group APIAVote in spring 2022. For the midterm elections in Pennsylvania, about 74% of AAPIs voted Democratic for Senate and governor, an exit poll by the Asian American Legal Defense and Education Fund found.

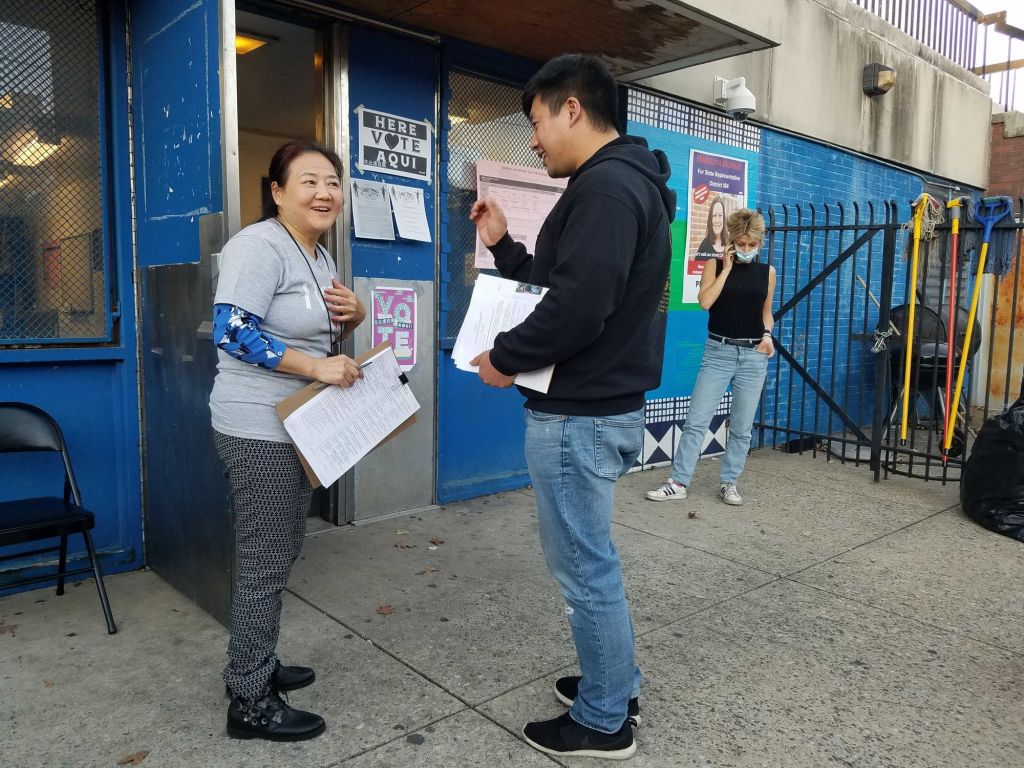

Translator Christie Yang (left) at a Philadelphia polling station on Nov. 8, 2022. Philadelphia joined several other US cities in offering new multilingual voting information and assistance this Election Day.Photograph: Amy Yee

Community Organizations’ Crucial Role

Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders are the fastest growing racial group of eligible voters in the US, according to the Pew Research Center, with 13.3 million AAPI voters across the country. In Pennsylvania, the number of eligible AAPI voters grew 55% from 2010 to 2020, compared to 3% for the statewide voting population, according to APIAVote, and that 39% of Asian American adults in the state have limited English skills. Some newer citizens might hail from authoritarian countries and need guidance on navigating elections.

Yet AAPIs are a largely untapped electorate who can nevertheless be the margin of victory in close races. In the 2020 elections, AAPIs cast 65,000 votes in Georgia, which President Joe Biden won by 12,000 votes. That year in Pennsylvania, they delivered about half of the Biden’s 80,000-vote margin of victory.

For months, Philadelphia nonprofits such as AAU, Southeast Asian Mutual Assistance Association Coalition (SEAMAAC), VietLead and others have helped register, educate and mobilize Asian American voters, and ensured they could vote this Election Day. Nonpartisan SEAMAAC, founded nearly 40 years ago, held events combining voter registration, Covid-19 testing, food distribution and other social services in South Philadelphia. It made use of well-trafficked neighborhood spots including a laundromat, a restaurant supply warehouse and a Cambodian temple, said David Pashley, a civic engagement consultant, and Dominic Brennan, SEAMAAC’s volunteer coordinator.

Thoai Nguyen, SEAMAAC’s chief executive officer, noted that the manager of the laundromat was a former SEAMAAC client and had already offered to store supplies for the organization’s hunger relief work. During the pandemic, the nonprofit distributed 7,000 meals and grocery bags each week as food insecurity surged. “SEAMAAC’s deep roots and relationships that we have built over many years by providing services, makes it easy for us to register voters,” said Nguyen. “We don’t have a partisan agenda and that helps a lot. People trust that more.”

Other grassroots groups across the state connected with diverse AAPI voters, such as Bhutanese refugees in central Pennsylvania.

Leading up to the 2022 midterm elections, the Pennsylvania group Asian Pacific Islander Political Alliance (API PA) and its partners ran the largest state-level AAPI voter outreach program in the country. Staff and volunteers reached 62,000 AAPI voters in 15 languages via 2.5 million phone calls and 140,000 door knocks. Some 25,000 calls were fully in Asian languages and reached more than 1,700 voters who don’t speak any English, said Mohan Seshadri, executive director of API PA. About 78% of Asian Pennsylvanians speak a language other than English at home. API PA also sent 311,000 mailings to voters in four languages, and ran ads online and in ethnic media.

“Everybody who wrote off Asian American voters and said reaching this ethnically diverse community was too hard, or too expensive, or required too many languages to be worthwhile to engage was wrong,” said Chen of AAU, who is also a co-founder of API PA.

Multilingual outreach through diverse channels is key. For example, social media app WeChat is favored by many Chinese speakers while other communities such as Indonesians often rely on in-language Facebook groups.

Zoom webinars, ads and other outreach helped people vote by mail. In 2020, half of Asian American voters in Pennsylvania requested mail-in ballots, the highest percentage for any community. They had the second-highest vote by mail return rate of any community in the state, said API PA.

Youth turnout among AAPI voters was notably high, according to Nancy Nguyen, co-founder of VietLead, a nonprofit that works with the Vietnamese community in Philadelphia through its youth program and campaigns to stop ICE detentions, school bullying and gentrification. Young people are “understanding how voting translates into who is into office, what policies are put into place and the impact on their lives,” said Nguyen.

Underlying the work of many AAPI community organizations is the Wallace H. Coulter Foundation, which for more than a decade has quietly given game-changing funding to many groups. In spite of overall philanthropic underfunding of AAPI-focused initiatives, Coulter lay the groundwork for record AAPI turnout in recent elections. “What you saw in 2020 did not happen overnight,” said Christine Chen, executive director of APIAVote.

Making Sure Every Vote Counts

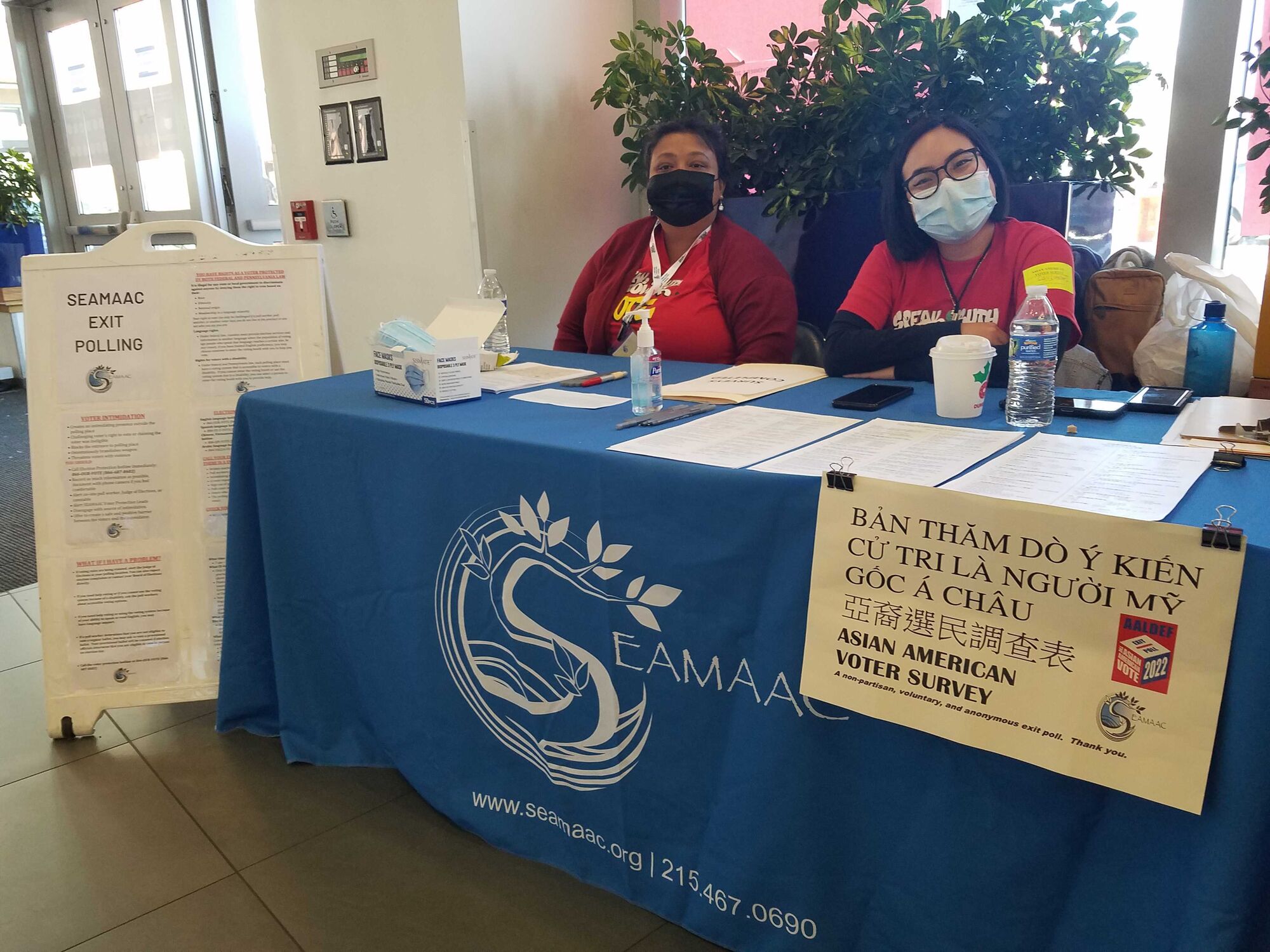

On Election Day, personal interactions and support can ensure a vote is cast or counted. At a polling site at the South Philadelphia Library, volunteers and staff from SEAMAAC sat at a table ready to assist.

Staffer Cali Tran helped an older Vietnamese American man with limited English proficiency at the voting machine — part of the Section 203 accommodations for limited English speakers.A Cambodian American elder also had questions, so SEAMAAC called a Khmer-speaking staff member who translated over the phone. A few Asian Americans approached SEAMAAC’s table to inquire about its weekly food pantry, a well-known resource in a neighborhood that home to one of the city’s largest AAPI populations. Many locals know and rely on SEAMAAC, founded in 1984 to serve Philadelphia’s Vietnamese, Cambodian and other immigrants. However, the nonprofit helps anyone in need; only about half of its clients are Asian. SEAMAAC offers services in 22 languages.

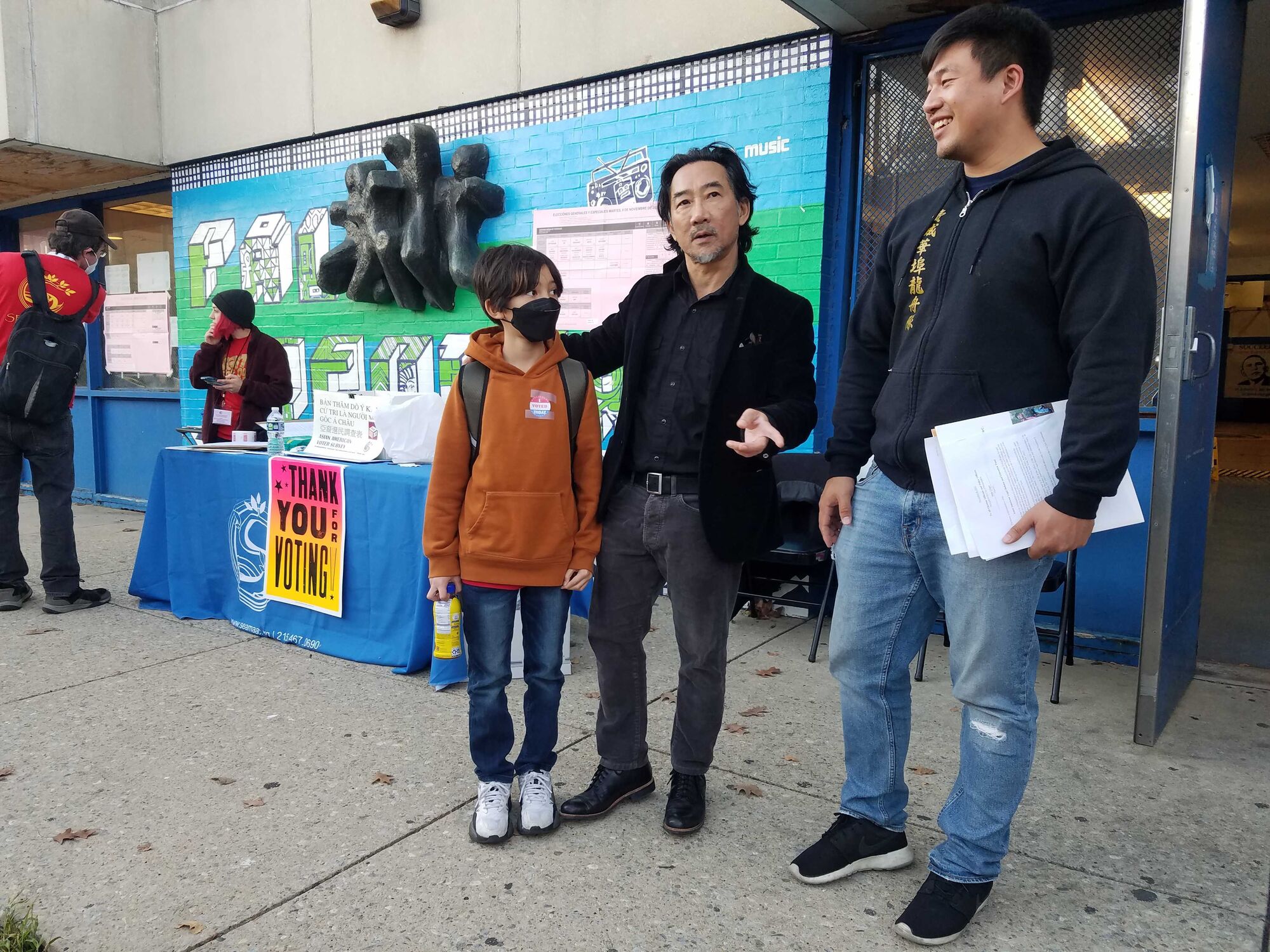

Thla Bawi, 36, came to the US from Myanmar in 2010. Outside another polling site in South Philadelphia, he chatted with SEAMAAC’s Nguyen. They knew each other because Bawi had participated in an entrepreneurship training program with the group. On Election Day, Bawi didn’t need help voting, but he recalled that SEAMAAC also helped him register to vote in 2020 elections. When asked why he took time off work to cast his ballot, Bawi said, voting gives a “right for my voice.”

Biak Cuai, a Burmese outreach worker at SEAMAAC, assisted outside a polling site at South Philadelphia High School. That morning she answered questions from five Burmese voters. The day before, she reminded two Burmese clients to vote. The couple put in long hours at a factory and warehouse, but with Cuai’s encouragement they promised to vote after work. “I feel so great,” said Cuai. “This is important for everyone.”

At South Philadelphia High School, Chen from AAU also helped Liu, a Fujianese speaker who asked only to be identified by his last name. Liu heard about AAU from social-media ads and got help to vote for the first time in 2020 via mail-in ballot. “Even though I don’t speak much English, I still want to participate in democracy,” said Liu, a restaurant worker in his 60s who immigrated to the US from China in 2002. He became a US citizen 10 years ago.

Gathering Data About AAPI Voters

In addition to organizing AAU staff and volunteers on Election Day, Chen worked as a poll monitor for the Asian American Legal Defense and Education Fund. The national civil rights group conducted the largest national exit poll of AAPI voters this year — spanning 15 states, including Pennsylvania — and monitored compliance with Section 203 in various cities. (It’s common for big exit polls not to include AAPIs, who are often lumped into the “other” category.)

Preliminary results from AALDEF’s survey showed that nationally in House races, 64% of AAPIs voted for Democrats and 32% for Republicans. And in Pennsylvania, support for Democrats in Senate and gubernatorial races was even higher at 74%. Top factors influencing their vote were the economy and jobs, health care and education. More than 21% had experienced anti-Asian harassment in the past two years, and 83% supported teaching AAPI history in schools.

AALDEF’s poll of 5,351 AAPI voters was conducted in 11 Asian languages:, including Arabic, Bengali, Chinese, Gujarati, Hindi, Khmer, Korean, Punjabi, Tagalog, Urdu and Vietnamese. Community groups like SEAMAAC and AAU also assisted people with filling out the survey outside polls.

Across the US, AALDEF found violations of Section 203, such as sites with no interpreters and other problems. In Philadelphia, there were glitches at various voting stations, such as no translators, signage or instructions in Chinese.

“Too many Asian American voters were required to provide identification when it was not required, were sent to the wrong poll site, were not given provisional ballots, and did not have access to interpreters,” said Jerry Vattamala, director of AALDEF’s Democracy Program. In Philadelphia, there were glitches at various poll sites such as no signage or instructions in Chinese.

In South Philadelphia, Mandarin speaker Vittorio Cho, 85, was a poll worker at Ford Pal Recreation Center. Cho is a US veteran who wants to “serve this country in any capacity,” he said of his work on Election Day.

Christie Yang, who normally works as a psychoanalyst, served as an interpreter at the voting site. By mid-afternoon, Yang had assisted eight people, including two Chinese American women whom she walked to their correct polling site 15 minutes away. She also helped an Asian American couple in their 90s vote for the first time. She recalled they were nervous, had poor vision and ran into trouble when a poll worker didn’t set up the voting machine correctly for them. But that didn’t stop them from casting their ballots.

“I was touched,” said Yang. “They understand it is very important to vote.”

As dusk fell, more voters entered the rec center and approached many tables inside a large gym. One veteran poll worker didn’t even know there were Chinese translators on site to help the whole day.

Yang was not aware that limited-English speakers could ask a SEAMAAC volunteer outside to help them in the voting booths if needed. She also noticed that another polling site, the Chinese translator was out of sight in a corner and not readily accessible.

“It’s important to have a Chinese interpreter,” said Yang of Philadelphia’s new federal elections mandate. “But it will take time. It’s not easy.”

A Philadelphia polling station offered multilingual “I Voted” stickers in English and Chinese and other languages such as Vietnamese and Russian.

Photographer: Amy Yee