A cultural landmark in Vancouver Chinatown opens July 1, the 100th anniversary of Canada’s Chinese Exclusion Act.

By Amy Yee

June 30, 2023

In the gleaming new Chinese Canadian Museum in Vancouver’s Chinatown neighborhood, photos of early Chinese migrants to Canada greet visitors from towering displays. Their visibility is a stark contrast to policies that once sought to repress them. One wall is covered with enlarged newspaper articles from the 1920s, with headlines like “Must Bar Oriental Completely to Save [British Columbia] for White Race,” and “‘Chinese Humiliation Day’ on July 1.”

The date refers to July 1, 1923, when Canada’s Chinese Exclusion Act came into effect and barred most immigration from China until 1947. The Chinese Canadian Museum’s opening in its permanent home on Saturday — also the Canada Day holiday — coincides with the 100th anniversary of the Chinese Exclusion Act. The restrictive immigration law and its human impact is featured in the museum’s opening exhibition.

The new cultural institution in Vancouver’s historic Chinatown is the first government-funded museum in Canada focused on a racial or ethnic group, said Melissa Karmen Lee, chief executive officer of the Chinese Canadian Museum. Plans for the landmark space were announced in 2017 as part of a reckoning for past discriminatory policies on Chinese immigration. Canada’s prime minister in 2006 issued an apology for those racist regulations.

British Columbia has since provided more than C$48.5 million ($33.7 million) to the museum, while private donors raised C$25 million. This May, the federal government pledged another C$5.18 million.

Its launch comes at a time when advocates are trying to save one of Canada’s oldest Asian enclaves from decay. Community leaders hope cultural anchors like the museum will bring visitors back to Vancouver Chinatown and help revitalize local shops and restaurants in the historic neighborhood. It joins other nearby tourist attractions such as the Dr. Sun Yat Sen Classical Chinese Garden and the Chinatown Storytelling Centre, which opened in 2021, mid-pandemic. Across North America, advocates for other Chinatowns are also trying to revitalize beleaguered neighborhoods.

The museum aims to help visitors understand how Chinese Canadians, “along with many other immigrants from around the world, have helped build and transform Canada” into a diverse and multicultural society, said Vivienne Poy, the country’s first Chinese Canadian senator.

A smaller temporary museum space in Vancouver Chinatown opened in 2020 during the Covid-19 pandemic, amid a spike in anti-Asian racism that worsened the neighborhood’s economic decline. More than 14,000 people have visited the temporary site since then, according to the Chinese Canadian Museum.

The museum’s new home in Chinatown’s oldest building — the Wing Sang Building at 51 East Pender Street — is fitting. The heritage site was built in 1889 by pioneering Chinese Canadian merchant Yip Sang, who became an influential business leader.

Vancouver real estate marketer Bob Rennie bought it in 2004 and restored it as an office and art gallery space. The building boasts 40-foot-high ceilings and spans 21,000 square feet. It is nearly twenty times larger than the temporary space next door.

Along with gallery exhibitions, the Chinese Canadian Museum will feature a period school room where Sang’s 23 children were educated, along with other students from the community. A blackboard still has writing in chalk from the 1960s. The top floor will also showcase a period living room with antique objects that re-create the 1930s, when Sang’s children and grandchildren lived in Chinatown. Outdoor films will be screened on a rooftop lawn that commands views of buildings built more than a century ago.

A New Life for Certificates of Identity

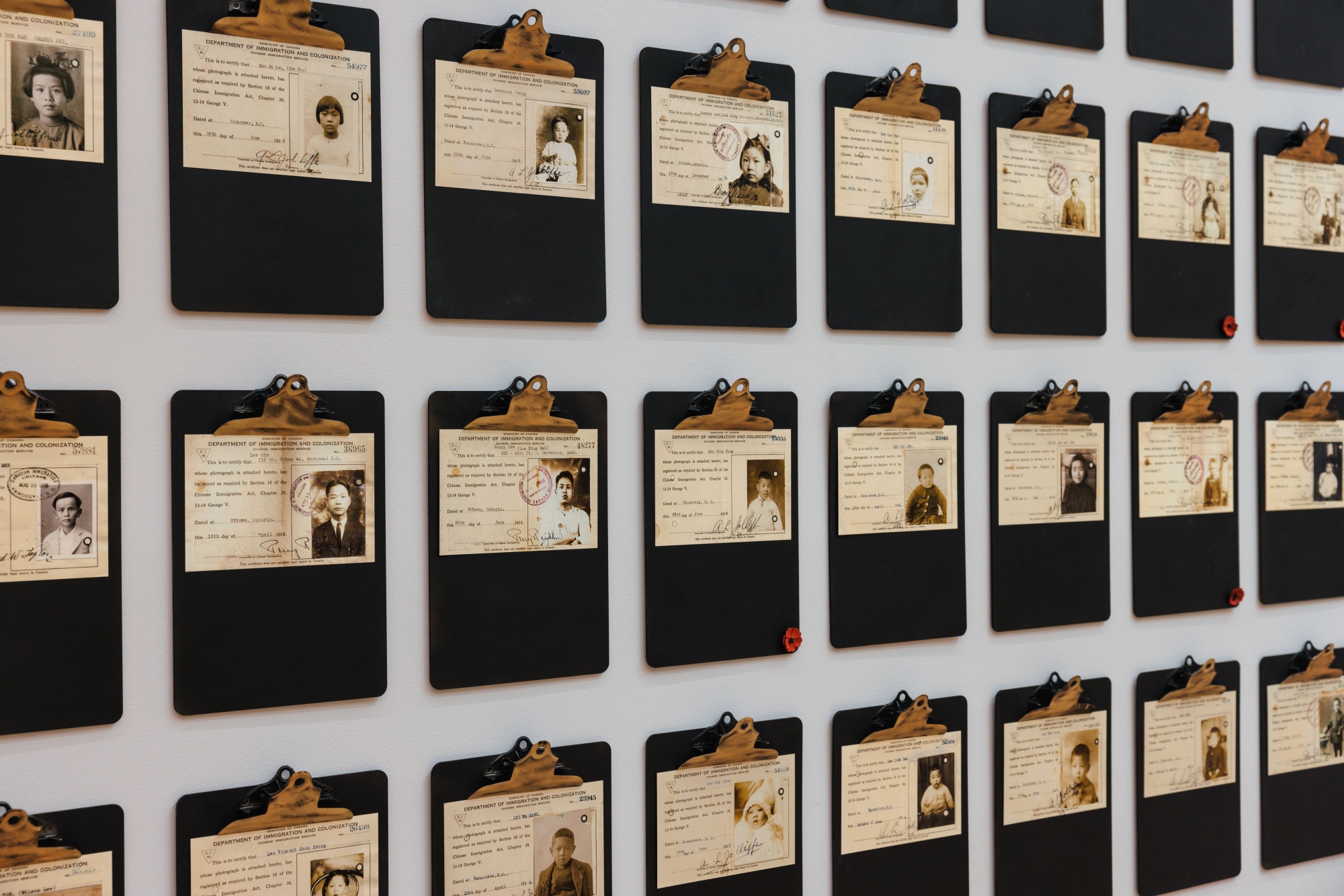

The inaugural exhibition, “The Paper Trail to the 1923 Chinese Exclusion Act,” shines a spotlight on early Chinese migrants. The faces of those who came to Canada in the 1800s to work in gold mines, build railroads and toil in other arduous jobs were captured in “certificates of identity” required only for Chinese people.

These government-issued documents for Chinese migrants “were intended to control, contain, monitor and even intimidate this one community,” wrote curators of the exhibition. The documents were a “constant reminder of a second-class status in Canada.”

More than 15,000 Chinese came to Canada to build the Canadian Pacific Railway. They were paid half as much as white workers and tasked with the most dangerous work, such as handling explosives, according to the British Columbia government.

Many identity documents were lost or destroyed over the years. Surviving ones were stowed away and forgotten. But three years ago, a research team asked Chinese Canadian families to contribute certificates for the exhibition.

Those photos and accompanying stories are featured on some 140 wall-mounted clipboards that can be perused individually. Certificates bearing faces and names such as “Charlie Chow C.I.36 Moose Jaw, SK” and “Kwan Kwai C.I.30 Vancouver, B.C.” are now memorialized for posterity.

About 400 scans of CI documents were collected and will be housed in a public online archive at the University of British Columbia.

“Through these aging, fragile pieces of paper we can learn the story of the individual who owned it; the struggles of an early immigrant community; and the story of a dark period in Canadian history,” wrote the curators on their website.

One photo in the exhibition shows Tai Hing Gom, 42, who was admitted to a British Columbia “lunatic asylum” in 1923. For some, “the decades of toil, struggle, separation and failed dreams became too much to bear,” explains a wall note. “They withdrew and grew despondent. Some stopped speaking or caring for themselves.”

Railroad companies promised workers return fare to China, but those pledges vanished after the Canadian Pacific Railway was completed in 1885. Many Chinese migrants could not go home and were separated from their families.

The museum pays tribute to the price that many Chinese migrants paid. After the Canadian Pacific Railway was finished, Chinese migrants had to pay a high “Head Tax” to enter Canada, which discouraged their immigration to Canada. The federal government in 2006 announced reparations of C$20,000 to living Chinese Head Tax payers and spouses of the deceased.

At last, the museum spotlights the contributions and hardships of Chinese immigrants who were once relegated to shadows.

“We tell stories that are hidden, and from a different perspective,” said Lee. “It’s the life’s work of museums to tell these stories.”